This month, Yale University released a digital tool that allows the public to search old Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographs by county. If you’re so inclined, you can step back in time and view your ‘hood as it looked 70 years ago. Pretty cool, right?

You know what's even cooler? You'll notice a lot of the first names in the footnotes for these photos are female.

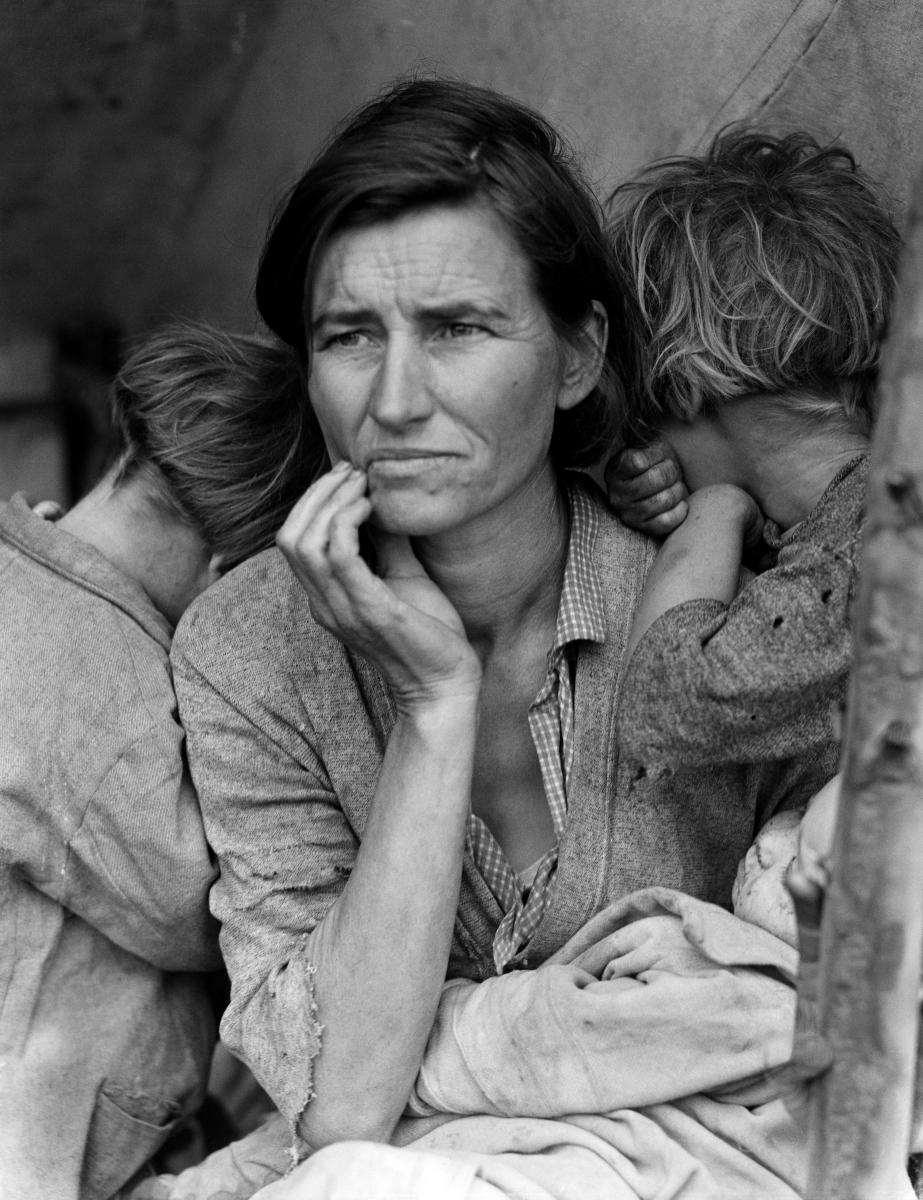

You no doubt covered the New Deal in high school or college, but let’s recap anyway—the FSA was a New Deal program created to lend a hand to poor farming families who fell on hard times during the Depression. The FSA was a pretty progressive program for its time—not only did it extend economic relief to the poor (an idea that still spooks some people), it relied on art to rally public support. In order to get the ball rolling, the FSA dispatched a team of photojournalists to rural areas to document the daily lives of the communities the FSA would benefit. This photography program inadvertently produced some of the most iconic American images; the kind that live as posters in museum gift shops everywhere. For example, there's this one, this one and of course, Migrant Mother.

The photojournalists that produced these enduring images were a small, but ultimately mighty, crew. Though their photographs are famous, most of the photographers behind them faded into obscurity. What they might not have told you in class is that a number of those photographers were female.

Women had been involved in journalism and photography here and there, but aside from a few notable exceptions (Google Nellie Bly or Ida B. Wells one of these days and get inspired), girls who yearned to document the world around them were generally relegated to puff pieces—fashion shows and advice columns, and in the case of photography, studio work. Owning a studio is certainly nothing to sniff at, but the work the female FSA photographers did was a huge step in allowing women to get down and dirty with the boys, in the uncomfortable, sometimes dangerous world of journalism and beyond.

In their honor, let’s take a peek into the remarkable lives of the women of the FSA.

Dorothea Lange

Born in New Jersey in 1895, Dorothea Lange had polio as a kid, which left her with an obvious limp for the rest of her life. Yet she still managed to live an incredibly full life devoted to photography: After opening a portrait studio in San Francisco in 1918, where she photographed the city’s moneyed upper class, she turned her attention toward migrant workers when the effects of the Depression began to creep west. She took the photos while her husband, an economics professor at Berkeley, recorded interviews and organized data. Lange’s most famous photo, Migrant Mother, was taken in Nipomo, California in 1936.

“I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions . . . She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.”

- Popular Photography, 1960

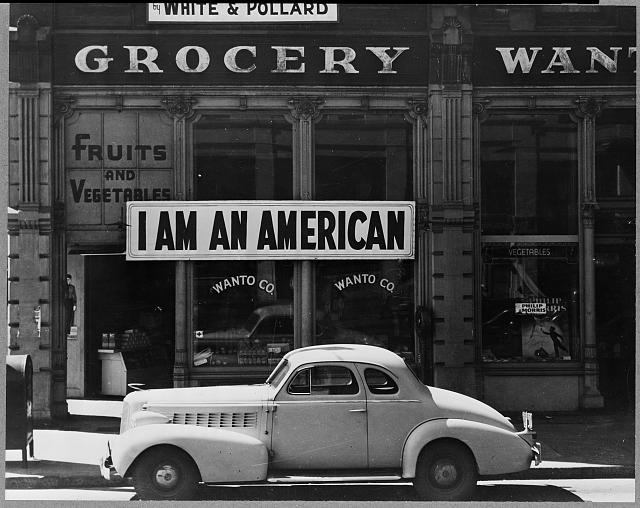

Once the economy started to bounce back and Americans turned their attention toward overseas conflicts, she pointed her lens at the residents of Japanese-American internment camps in the West. Though her photos were originally confiscated by the Army for being too "controversial," they’re now in the National Archives.

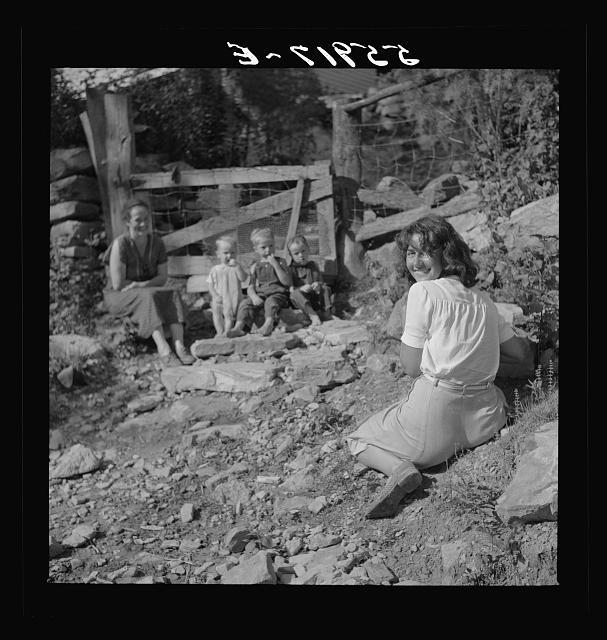

Marion Post Wolcott

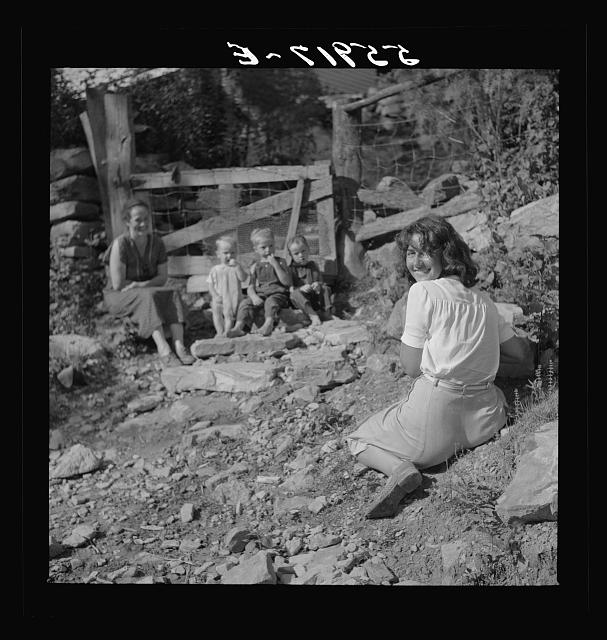

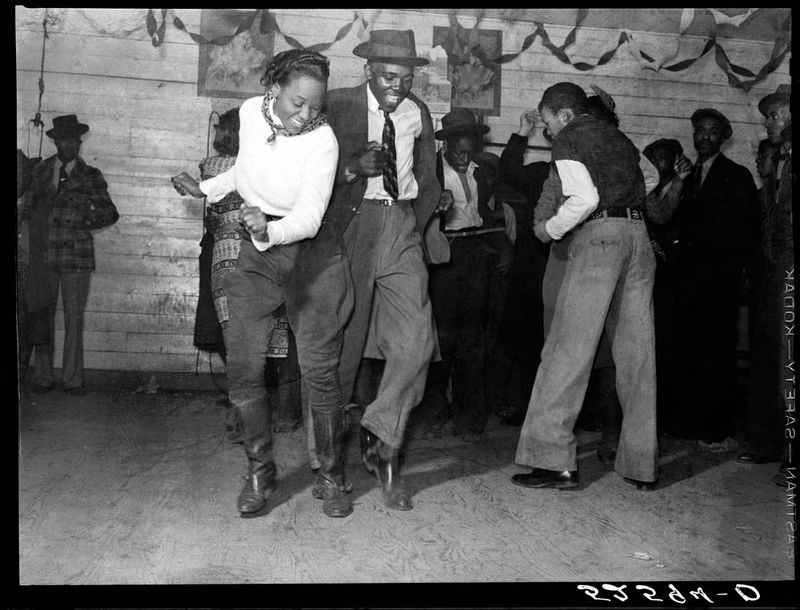

Marion Post Wolcott was the FSA’s workhorse, producing over 9,000 (print!) images in four years. Born into an activist family in New Jersey (her mom worked with Margaret Sanger to establish birth control clinics around the U.S.), Marion spent her early 20s studying abroad in Vienna, where she came face to face with the rising terror of the Third Reich. She returned home in 1934 with a renewed sympathy for underserved, persecuted and ignored communities, and after taking a job as a rare female staff photographer at the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, she joined the FSA in 1938. Her photos focused mostly on poor, rural African-American communities in the South and coal-mining families of Appalachia, where her cherubic face, her curly hair, her ability to change a tire, and her love of long pants set her apart from the pack.

"I just wish you had been along with me for just part of a day looking for something, particularly with POCKETS. Let us assume that we agree on the premise that all photographers need pockets—badly—+ that female photographers look slightly conspicuous + strange with too many film pack magazines + rolls + synchronizers stuffed in their shirt fronts, + that too many filters + what nots held between the teeth prevent one from asking many necessary questions. Now—this article of clothing, with large pockets, must also be cool, washable if possible, not too light or bright a color. Try + find it!"

- Letter to Roy Stryker, 1939

Louise Rosskam

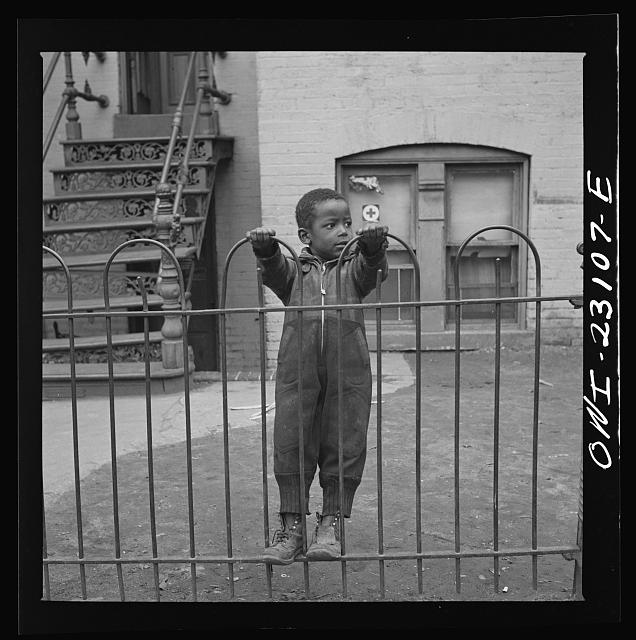

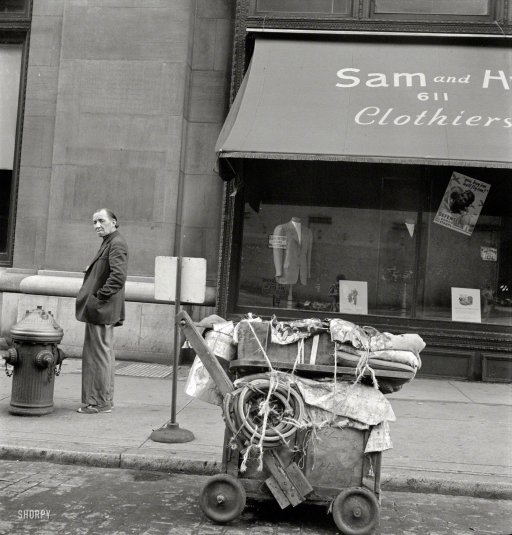

Before coming to the FSA, Louise Rosskam had been turned down for a position at the Philadelphia Record—both she and her husband Edwin had applied, but when they refused to hire her, he listed her wages as “gas and oil” on his expense reports. After producing a few photo books, where only Edwin’s name appeared in the byline, the FSA hired both of them in 1939. Her first photographs were distinctly urban images of crowded, cramped city life, taken in her backyard of Washington, D.C, that highlighted the integration in her community.

"We moved into an area of Washington that looked very nice and I've never, you know, I could have passed 10,000 alley dwellings and never seen them . . . [but] with a camera it means you have to talk to the people and you suddenly see an alley dwelling. There it is, these people are alive and living in it, it becomes something completely different. It's there and you—it becomes part of you and you can't run away from it any more once you are actually faced with it. And the next best thing to that is seeing it in a photograph. " -Interview with the Archives of American Art, 1965

Make no mistake, Louise was never Edwin’s assistant or secretary—the photographs she produced are just as stirring and just as enduring as anything else in the FSA’s annals. The FSA was the first place to allow Louise to—gasp!—attach her own name to her own work.

Ann Rosener

Ann Rosener came on board a little later, in 1941. Though the economy was recovering, women were still expected to work—this time, as war workers. Rosener carved out a niche for herself photographing the women (and minorities and the disabled) who turned to factory work during the war. She took delight in showing women in elaborate hairstyles and smart dresses doing "men’s work"—and the many ways housewives helped the war effort at home. Rosener’s prints are now in the possession of the Library of Congress—and some of them are delightfully weird.

Esther Bubley

Fresh out of art school, 22-year-old Esther Bubley was another late addition to the FSA photography team—she joined in 1942, after the FSA had been discontinued and the photographers taken over by the Office of War Information. Bubley specialized in portraiture—while the world was distracted by the growing threat of war, she documented the mundane goings-on of small-town America, focusing less on the barren landscapes present in early FSA photos, and more on the colorful characters that lived on them.

Marjory Collins

Eternal iconoclast Marjory Collins was hired in 1941. Also assigned to cover home front life during the war, Collins found her niche photographing women and what she called “hyphenated Americans”—the immigrant communities that had settled in the United States, and especially those that came from countries the U.S. was sparring with overseas. Later, like Rosener, Collins focused on women in industry and the struggles they faced as they tried to balance societal demands levied against them as both workers and wives.

Collins kept up with social causes after the war, and was a prominent participant in anti-war protests and equal-rights rallies in the 1960s. When she was forced out of her full-time job as a magazine editor through ageist, sexist means, she went on to found a new publication aimed at older women called Prime Time.

Images: Wikimedia Commons/Library of Congress/Shorpy.com